A study found that high-salt diet in mice altered the immune response in their gut, leading to a reduction in blood flow to the brain, neurovascular dysfunction and cognitive impairment.

These harmful effects occurred independent of elevation in blood pressure. Measurable deficits in brain function were observed even though there was no change in blood pressure.

However, returning the mice to a normal diet reversed these negative effects in brain vascular dysfunction and cognitive impairment. The study was reported in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

Background

Processed foods and western diets are packed with salt. Average daily salt intake in the US is more than 3.4 grams (equivalent to 8.5 grams of table salt), even though guidelines recommend an intake of less than 2.3 grams (5.8 g of table salt).

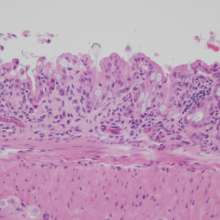

In humans, a salt-rich diet is known to cause high blood pressure and increase the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases. At the cellular level, excessive salt consumption leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells, the cells that line blood vessels and regulate vascular tone (flexibility and strength, for example).

Previous studies have shown that high salt intake increases the number and activity of immune white blood cells called T lymphocytes, especially a pro-inflammatory subset called TH17 cells.

Activated TH17 cells produce the immune signaling factor interleukin-17 (IL-17), which promotes hypertension and inflammation in blood artery walls, and induces autoimmune diseases.

This study further shows that it was the increase in circulating IL-17 with the high salt diet that caused brain vascular dysfunction and brain function impairment.

The study

Researchers at the US Weill Cornell Medicine research institute fed mice a high-salt diet comparable to the excessive proportion of salt found in some human diets.

Within a few weeks, the salty diet led to endothelial dysfunction, a reduction in cerebral blood flow, and cognitive impairments in several behavioral tests, but no changes in blood pressure.

In line with previous studies, the salty diet also increased the numbers of TH17 immune white blood cells in the gut and the levels of a pro-inflammatory molecule IL-17 these cells released.

Significant alterations in cognitive function that involved multiple domains were induced. But these harmful effects were reversed by returning the mice to a normal diet, or by pharmacological intervention.

Implications

Importantly, the harmful effects of the salty diet were reversible, suggesting that a change in lifestyle or new prescription drugs could help reverse or prevent these effects.

Although these results were obtained in mice, the study also shows that IL-17 affects human cerebral endothelial cells similarly. The researchers suggest that a high-salt diet may also negatively impact brain health in humans, regardless of its effect on blood pressure.

Note:

For more on the effects of high salt diet on immunity, refer to the article High salt diet kills beneficial gut bacteria