It is estimated that over 50 million Americans suffer from allergies or asthma, and that many of them seek treatment with allergen-specific immunotherapy, or allergy shots. Unlike antihistamines or corticosteroids, which temporarily relieve allergy symptoms, a three to five year regimen of allergy shots can permanently reduce a person’s sensitivity to environmental allergens.

How allergy shot works

Though the effect of allergy shot, or allergen-specific immunotherapy, was first observed in 1911, scientists are still unraveling the mechanisms behind this type of immunotherapy.

When the immune system detects a foreign body, a type of white blood cell called the T helper cell is activated. The T cells respond by releasing molecules called cytokines, which signal other cells to behave in ways that will help fight the infection. The primary types of T cells are TH1 cells, TH2 cells, and Treg cells, which are distinguished by the types of chemical signals that they emit and the types of pathogens that they respond to.

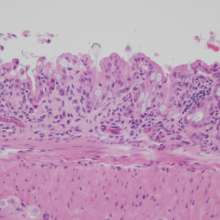

Allergy symptoms are the result of a TH2 immune response. TH2 cells stimulate the production of IgE antibodies, which bind to the allergen and trigger the release of histamine and other chemical signals that lead to classical allergy symptoms, such as the production of mucus.

In contrast, TH1 cells stimulate the production of IgG antibodies, which bind to the foreign body but do not stimulate the release of histamines. Treg cells are responsible for “regulating” the immune response by emitting anti-inflammatory cytokines and suppressing the other T cells.

A matter of balance

It is believed that the balance between the different immune responses is critical in our understanding of the development and treatment of allergies.

Allergic individuals possess a higher ratio of TH2 cells than non-allergic individuals, and it has been demonstrated that allergy shots can help produce additional Treg cells. In addition, injection of the allergen has been shown to increase the number of IgG antibodies 10 to 100 fold. These IgG antibodies bind to the allergens, which makes them unavailable to bind to IgE antibodies thus preventing the release of histamines.

While allergy shots are effective in reducing symptoms over the long term, there are downsides to this treatment. Severe anaphylactic reactions can occur after injection of even a small amount of allergen, and the requirement of weekly or monthly shots over the course of three to five years places a high burden on patients.

Scientists are hoping that a better understanding of the mechanisms behind immunotherapy will allow them to develop new treatments that address these concerns.

Currently, a method of administering the allergen under the tongue rather than via injection is being studied. In addition, scientists are studying the effects of using allergen fragments or hybrid allergens to reduce the risk of an anaphylactic reaction.