Can swearing increase physical power and strength in sports performance? Researchers reported in the Journal of Psychology of Sport and Exercise that the answer is positive.

Background

Offensive or obscene language, known as cursing in the US and swearing in the UK, is a near-universal feature of human language. To swear may be defined as to utter a word or phrase that is considered taboo, or forbidden.

It is the swear words or phrases themselves that are taboo rather than the semantic meanings they convey. So, for example, talking about sexual intercourse need not of itself be obscene, however the word “fuck” is a well-recognized swear word deemed “very severe” by 71% of 1033 respondents in a national UK survey.

Nevertheless, there is no universal agreement as to which words are swear words and the same survey found that 9% of male responders and 4% of female responders deemed “fuck” to be a mild swear word or not a swear word at all.

While it may be difficult to define exactly what differentiates swearing from words that are just unpleasant, most people understand what swearing is. When asked to nominate the swear words they most often use, a sample of Dutch students provided strikingly similar examples, with “shit” and “cunt” nominated by 80% and 75% of respondents respectively.

This shared cultural understanding of swearing has enabled researchers to study why people swear and what functions swearing may have.

For example, a study suggests four functions of swearing: social swearing (as a marker for in-group solidarity), abusive swearing (which is self-explanatory), stylistic swearing (the use of bad language to make what is being said sound more enticing), and swearing as an emotive response (to frustration or the unexpected).

One common source of frustration is acute pain arising from accidental injury. Research has found that, for most people, swearing in response to pain reduces pain perception. Participants repeating a swear word have been shown to withstand an ice-water challenge for about 40 seconds longer, on average, compared with those repeating a non-swear word.

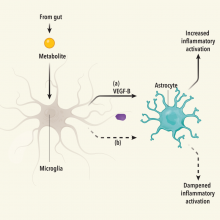

Swearing represents an extreme form of emotional language, which might have activated the sympathetic nervous system facilitating a stress-induced analgesia. This would have led to the release of several neurotransmitters including the catecholamines epinephrine and nor-epinephrine.

Catecholamines act to raise heart rate and blood pressure, providing greater oxygenation to working muscles such that muscle force production improved with increased levels of catecholamine release.

Given the links between swearing, sympathetic activation and the subsequent release of epinephrine and nor-epinephrine, the researchers seek to determine whether swearing can increase physical performance with similar physiological changes.

The study

This study examines two scenarios. In experiment one, a high-intensity 30-second anaerobic cycling power challenge was employed. In experiment two, an isometric handgrip strength task was performed.

The experiments examined how swearing affected strength, power, and cardiovascular and autonomic functions in men and women.

Results

Swearing produced a 4.6% increase in initial power during the 30-second stationary bicycle test, and an 8.2% increase in the test of maximum handgrip strength.

However, swearing did not affect cardiovascular or autonomic function assessed via heart rate, heart rate variability, blood pressure and skin conductance.

Study results show that strength and power in sports performance increased with swearing. But the absence of cardiovascular or autonomic nervous system effects makes it unclear whether these results are due to an alteration of sympathovagal balance or an unknown mechanism.