Both shingles (herpes zoster) and chickenpox are caused by the same virus varicella. But shingles can potentially cause nerve damages and serious degradation of the quality of life.

Chickenpox

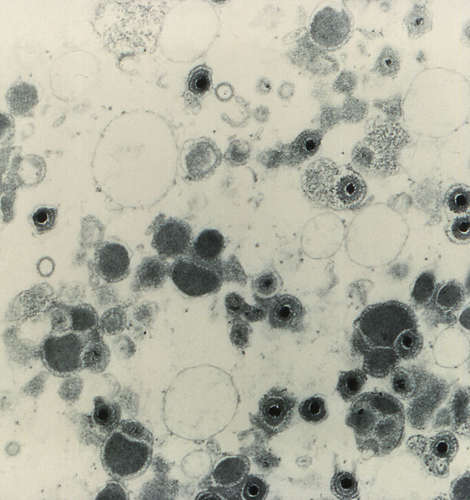

Chickenpox is caused by a herpes virus known as varicella-zoster virus (VZV). In temperate climates, such as in Canada and the US, more than 90% of children under age 15 have had the disease and about 95-98% of individuals have been infected by adulthood.

VZV released from a person with chicken pox can infect another individual via inhalation into the respiratory tract. During its incubation period (10 – 21 days), the virus proliferates while spreading to lymph nodes, liver and spleen. Then it enters the skin where it typically produces a rash with vesicles that appear mainly on the trunk, face and scalp. Infection can also spread by VZV present in the vesicles.

A person who has chickenpox is set up for the possibility of shingles in the future because VZV proliferating in the skin during chickenpox invades nerve cells in the skin.

Areas of our skin are innervated by the branches of a specific nerve emanating from the spinal cord. After VZV enters the endings of sensory nerve cells that compose the nerves located in the skin, it localizes in the nucleus of these nerve cells.

After the chickenpox disease has run its course, the virus located in the nerve cells become dormant and can remain dormant for life until, under certain circumstances, they are reactivated.

Reactivation of VZV causes shingles

Reactivation of the VZV in the nerve cells is dependent on the effectiveness of the immune system. After experiencing chickenpox, an individual develops immunity both against another case of chickenpox as well as reactivation of the dormant VZV.

This immunity depends in part on antibody production and in part on certain cells of the immune system that directly attack the VZV.

Immunity is boosted when the individual periodically comes into contact with children infected with chickenpox. However, as an individual ages, the immunity, particularly the cell-mediated immunity, begins to weaken naturally.

The VZV that had been dormant, usually for decades, may be reactivated, proliferates and produces the tissue damage and inflammation that cause the characteristic features of herpes zoster (shingles).

In addition to ageing, other factors that reduce the efficiency of the immune system may also induce reactivation of VZV. These factors include, among others, immunosuppressive drugs, organ transplantation, AIDS, chronic steroid therapy, trauma, and stress.

Features of shingles

Reactivation of the dormant virus usually occurs in the nerve cells of only one of the nerves innervating the surface of the body. Like in chickenpox, the first visible sign of shingles is a skin rash.

This rash appears on one side of the body only. It is usually localized to the specific part of the body that is associated with the nerve in which the VZV was reactivated.

About 2 (or more) days before the characteristic shingles rash appears, the patient usually experiences pain, skin sensations such as burning and itching, headache and flu-like symptoms.

The rash becomes more extensive over 7 to 10 days with clusters of vesicles that eventually form pustules, which scab and heal within 2 -3 weeks.

Location of the rash depends on the location of the nerve in which reactivation of the virus occurs. The thorax is the most common location for the appearance of the rash but other regions of the body can be involved, including the face and neck.

The vesicles of shingles patients contain VZV that can be transmitted and cause chickenpox in a person who has not previously had chickenpox. But the virus will not cause chickenpox nor shingles in a healthy person who has already had chickenpox.

In fact, exposure to the VZV is thought to boost immunity to the virus. However, about 5% of individuals who have had one episode of shingles experience another.

Nerve pain

The most distressing aspect of shingles is the pain suffered during and after the course of the disease due to neurological damages caused by the virus.

Acute pain accompanies the rash in 60-90% of patients and generally lasts for about 30 days after the onset of the rash. The intensity and duration of pain varies between individuals and produces varying effects.

Some studies show that older individuals who still had pain at 30 days had significantly poorer physical, emotional and social functioning. A more difficult problem is that of postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), which is defined by some researchers as shingles pain that lasts for at least 120 days, long after healing of the rash.

This pain can be intermittent or continuous, throbbing or stabbing, and in some cases even the slightest touch will evoke pain. PHN is more common and severe in older individuals. In one study of patients over 50 years of age, almost 40% had pain at 180 days. In some cases, the pain lasts for years.

PHN can have a devastating effect on the quality of life: in a British study, 59% of patients with PHN were unable to carry out their usual activities for an average of 1.4 years, with a maximum of 16 years.

Incidence of shingles

It is estimated that in the US, there are approximately one million new cases of shingles per year. The lifetime risk of developing shingles is about 25%, but in persons older than 60 years, risk is higher than 50% , and about 50% of persons who reach the age of 85 will have had shingles.

The incidence of shingles increases with age:

<50 years 2/1000 persons/year

50-59 years 4.6/1000 persons/year

60-69 years 6.9/1000 persons /year

>80 years 10.9/1000 persons /year

Similar rates occur in other parts of the world.

Treatment

Antiviral drugs when administered within 72 hours after the first appearance of the rash have been found to hasten healing of the rash and to decrease the severity and duration of acute pain. However, in many cases, the disease is not diagnosed early enough to benefit from antiviral drugs.

In the case of PHN, timely treatment with antivirals does appear to reduce the risk for chronic pain in some patients. In some studies, it was found that 20% of patients over 50 years of age treated with antivirals within 72 hours of rash onset still had pain 6 months later.

There is some evidence that treating acute pain with various analgesics to reduce the acute pain may reduce the risk for PHN. Use of these drugs must be balanced against potential adverse effects.

Prevention

In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration in the US licensed an injectable vaccine, ZOSTAVAX™ , developed by Merck & Co for the prevention of herpes zoster (shingles).

The vaccine is a preparation of live (active) VZV that causes chickenpox but which has been attenuated . (“Attenuated” refers to the fact that the VZV has been modified by genetic engineering so that it will not cause the disease but will still stimulate the immune system to neutralize any naturally-occuring VZV infecting the individual.)

The original clinical trial of the vaccine included 38,546 subjects 60 years of age or older, who had had chickenpox. The study followed these subjects for an average of 3.1 years.

Compared to all subjects who received the placebo, those who received the vaccine had 51.3% fewer cases of shingles. When evaluating the data by age groups, subjects aged 60-69 years had a 63.9% lower incidence of shingles, and those 70 years and older had 37.6% lower incidence than in the placebo group. The vaccine reduced the incidence of PHN by about 66% in both age groups.

Early data indicate that the vaccine provides effective protection for at least 4 years and long-term surveillance may find that it lasts longer. Aside from irritation at the site of injection, no significant adverse effects were found.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in the US recommends a single dose of the herpes zoster vaccine for prevention of shingles in persons 60 years and older. Because the major clinical study did not include persons under age 60, there is no recommendation for them. Clinical studies are underway to test the vaccine in the 50-59 age range. In 2008 ZOSTAVAX was approved for use in Canada and available for distribution in 2009.

* See update on shingle vaccination and references.