According to new research that first quantified ice loss from the Amundsen Sea embayment of the West Antarctica, which hosts some of the fastest melting glaciers on the planet, hundreds of metres of solid ice were lost between 2002-2009.

The findings, published in the scientific journal Nature Communications, support the hypothesis that the influx of warm ocean water beneath ice shelves in the area significantly increased during the mid-2000s.

When warm ocean waters flow across the continental shelf into sub-ice shelf cavities, they slowly erode the ice, especially near the glacier's grounding lines where the glacier meets the sea.

However, until now, the exact magnitude of the ice loss has remained poorly quantified.

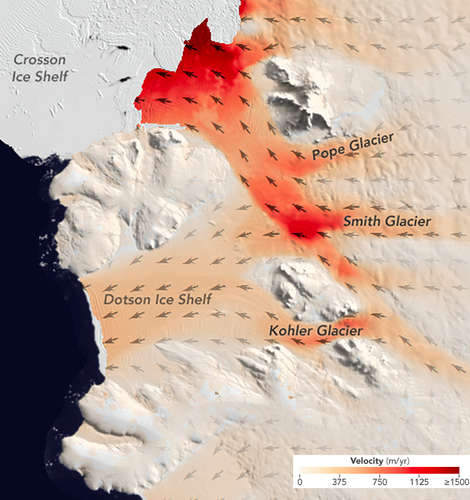

In this study, researchers use airborne radar sounding data collected by the NASA’s (US National Aeronautics and Space Administration) Operation IceBridge to examine the variations in melting rates and grounding line positions of three Antarctic glaciers in the Amundsen Sea embayment: Smith, Pope, and Kohler.

Data show intense, unbalanced melting of the glaciers between 2002 and 2009, with Smith Glacier losing as much as 70 metres per year, and almost half a kilometre of ice thickness in total.

Between 2009 and 2014 a reduction in the influx of warm ocean water led to less ice loss from Pope and Kohler. However, the grounding line of Smith Glacier retreated into a deep trough, contributing to continued intense ice loss.

The study suggests that regional scale, simultaneous change like this is most likely the result of increased temperature and/or flow of warm water in the sub-ice shelf cavities.

Findings demonstrate that the position of the retreating glaciers, along with the variability of oceanic heat influx, modulate the observed melting rates.

The researchers also pointed out that submarine ice loss in these rapidly changing areas is so large that they can now be measured directly with airborne radar sounding.